AFP action rectifies historical injustice

By: Ramon J. Farolan

February 15, 2016

For more than a century this falsehood, foisted on the Filipino people by colonial rule, was accepted by many chroniclers of the era.

Last month, as part of continuing efforts to rectify distortions in our military history, Armed Forces of the Philippines Chief of Staff Gen. Hernando DCA Iriberri paid tribute to Macario Sakay’s heroism and leadership in the struggle for freedom and independence from Spanish rule and American domination. He issued General Orders No. 30, renaming Camp Eldridge in Los Baños, Laguna, to Camp General Macario Sakay.

Background information

In 1902, US President Theodore Roosevelt issued a proclamation, officially ending what Americans referred to as the “Philippine Insurrection.” In his announcement, he declared that “peace had been established in all parts of the archipelago, except in the country inhabited by the Moro tribes.” I am thinking now that more than 100 years later, we have not been able to firmly establish peace in areas populated by our Muslim brothers, the same situation faced by Roosevelt.

The proclamation did not reflect the reality. It was issued mainly in response to domestic pressure from anti-imperialist elements in the United States. The American public was frustrated more than ever by the seemingly endless struggle in the Philippines, keeping in mind that the Philippine-American War started in February 1899. They were horrified by the slaughter taking place, particularly the Balangiga massacre of American soldiers in September 1901. Roosevelt feared that a prolonged conflict would damage his bid for reelection.

The surrender of Gen. Miguel Malvar in April 1902 provided the United States with a basis for declaring that the war was over. This position completely disregarded the resistance activities of Macario Sakay and other freedom fighters who continued the struggle against the new colonizer. As part of the US pacification effort, the US government branded Sakay and others as “bandits” and “tulisanes” to support the American propaganda line that the Philippine-American War was over and only common criminals were being rounded up and executed.

The so-called “insurrection” was expensive and bloody for both sides. The Americans spent some $600 million—or roughly $10 billion in today’s currency—and lost 4,234 men killed in action. (This is almost the same as the US losses in Iraq between 2003 and 2014.) Our casualties came up to some 20,000 soldiers and 200,000 civilians.

* * *

Who is Macario Sakay? What was his role in the fight for freedom?

It is important to know more about our heroes, particularly those whose reputations were tarnished by black propaganda depicting them as common criminals because of their anti-American activities.

Macario Sakay was born in Tondo, Manila, in 1870. He worked as a blacksmith, a tailor and a stage actor, before joining the Katipunan Movement led by Andres Bonifacio. During the revolution against Spain, he led his men to victory in San Mateo, Rizal, establishing his headquarters in the Marikina-Montalban area.

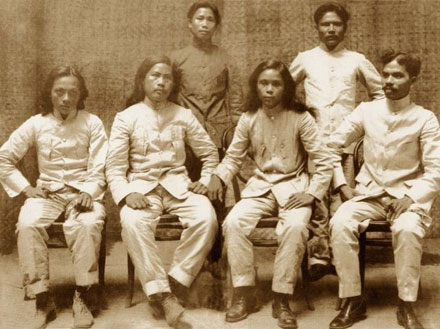

From 1902-1906, he continued the fight against the new colonizer, leading an effective guerrilla campaign against US forces. Vowing that he and his men would not cut their hair until freedom was achieved, Macario kept his locks long and this became a symbol of resistance. The “Sakay look” (long-haired and unkempt) was used by the Americans to portray him as a bandit and not a freedom fighter.

Sakay’s main area of operations was in the southern Tagalog provinces of Rizal, Batangas, Laguna and Cavite. So successful were his exploits that the Americans resorted to “hamletting” (concentrating villagers in one location for more effective control) in areas where Sakay had strong mass support.

Using an ilustrado, Dominador Gomez, to speak to Sakay, US Governor General Henry Ide offered him amnesty. Part of the offer was the establishment of a Philippine Assembly as a starting point toward eventual independence. The idea appealed to Sakay and as a result, he came down from his mountain redoubt and surrendered. It was a trap. Once he and his subordinates were disarmed, they were arrested and charged with refusing to give allegiance to the American government in the Philippines. Sakay was sentenced to death and executed.

His last words were: “We are not bandits and robbers as the Americans have accused us. We are members of the revolutionary force defending our mother country, the Philippines. Farewell! Long live the Republic! Long live the Philippines!”

* * *

Camp Eldridge was named after an American serviceman, Sgt. George Eldridge, a Medal of Honor recipient in the fight against American Indians in 1870. Renaming the camp after General Sakay is historically appropriate since the military facility is located in the Calabarzon area where Sakay operated against enemy forces.

More than just honoring one of our freedom fighters, the name-change is another step in bringing closure to the historical distortions that one can find in abundance in our military history. It is a difficult and tedious exercise often surrounded by controversy, but it must be done if we are to discover the truth about ourselves.

Recognitions

There are a few individuals and organizations who must be recognized for their efforts in bringing about this change.

• Lt. Col. Ronald Jess Alcudia, PMA Class 1993, through his writings in various Army publications, was able to call attention to the need for rethinking the Philippine military’s perspective of the post-1902 resistance movement, promoting a patriotic and nationalist viewpoint.

• Lt. Gen. Ernesto Carolina, as head of the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office, supported Alcudia’s advocacy.

• The Philippine Historical Association, in a board resolution, recommended to the Department of National Defense the renaming of Camp Eldridge after Gen. Macario Sakay.

• Gen. Hernando DCA Iriberri, as commanding general of the Philippine Army, and now AFP chief of staff, approved the recommendations for the proposed change and kept a close eye on the paperwork all the way to the highest levels of government. Change comes about when the leadership is sincere in its concern for renewal and rededication.

In a memorandum dated Dec. 28, 2015, final approval was issued by Defense Secretary Voltaire T. Gazmin.

Source: Philippine Daily Inquirer