By Cid Reyes

The Surrealist artist Max Ernst once narrated a story of his father, artist, who painted his garden from which he left out a tree for the sake of composition. However, he felt guilty that his painting did not reflect actual reality. Being scrupulously honest, he decided to cut down the tree.

On the other hand, the British critic David Sylvester shares that the French Impressionist Monet “did much the same sort of thing, though in reverse order. He, too, believed, that he ought to paint nature exactly as he saw it, without rearranging it in the painting to make it conform with an ideal of art. However, it is said that he sometimes paid workmen to lop branches off a tree before he began his painting of it, and certainly, once he had money enough to buy land, he had gardens and lily-ponds laid out in accordance with his designs and then painted what was there.”

These stories come to mind as one admires the landscape paintings of Lino Acacio. For decades, it has become a brand name associated with Batangas – yes, much as the names Botong Francisco means Angono, and Vicente Manansala synonymous with Binangonan.

Visionary Landscapes

Hailing from Lemery, the artist might as well be the Governor of Batangas, in the consistent way he has “commanded” the mountains, hills, valleys, and rivers of his birthplace to conform to his own visionary landscapes. This he accomplished without ordering the lopping off of branches, or indeed, the planting of more trees. Indeed, it is this relentless consistency and dominating passion to evoke the landscapes of Batangas, that has been the running motif of his artistic life, which commenced right after leaving his Fine Arts studies at FEATI University, with just a year to go prior to receiving his diploma. But nonetheless, it was a departure where Acacio brought with him the unconventional tutelage of the late Ibarra de la Rosa, a name forever engraved, likely as not, on the halls of that institution of learning, which university slogan was “Look up, young man, look up!”

And surely, bound to occur to many viewers is the question: are there residual influences of Ibarra de la Rosa, famous for his trademark brushstrokes, those bristling flecks of Fauvist primary colors, in the art of Lino Acacio? Whatever the answer, whatever influences there may be, have no doubt been subordinated to the then-emerging sensibility of Acacio, whose fervor for landscape painting had found expression in the rich harmonies of nature’s colors.

As extolled by his alma mater, Acacio did look up, and what he beheld appealed to his discerning aesthetic eye and emotional heartstrings, for he knew the subject that he was born to paint: the landscapes of Batangas. In fact, many young artists have struggled and despaired at ever finding their subject matter – some traveling around the world, in a manner of speaking – only to find it in his own backyard.

Spirit of Place

One senses that the difference between them and Acasio is this artist’s ability to see, beyond looking, to perceive not merely with the eyes, but through the gift of being emotionally moved and the capacity of being sympathetically touched, not only by what is visible but more importantly, by the invisible, which is nothing less than the spirit of a place, what is known as the genius loci, or distinctive atmosphere. Essential to this distinctive ambiance is the unique manifestation of form or expressive structure that is germane and organic to the artist, and that possesses its own rhythm of execution, stamped, as it were, with a graphic signature. This is easily proven by comparing Acacio’s landscapes with those of National Artist Fernando Amorsolo or Teodoro Buenaventura.

In no way would any viewer mistake one for the other. And neither is one the echo or shadow of the other. While it may look presumptuous to even compare the much younger Acacio to those two departed legends of Philippine landscape painting, the exercise is instructive. Interestingly, an Acacio work titled “Araw ng Pagpapala” may be an unwitting nod to Amorsolo’s “Going to Sunday Mass.” But in reverse: Acacio depicts parishioners wending their way back home after Mass, the church still visible from a distance.

Perhaps the one abiding stroke of luck for Acacio was being discovered by Galerie Genesis, founded by Ernie and Chi-Chi Salas. This enterprising couple was not only passionate for art – they are great collectors themselves – but was also innately compassionate to young Filipino artists. Also to this couple’s credit is the renaissance of appreciation of watercolor painting, mainly through their launching of the watercolor competition, Kulay sa Tubig. Thus, under the helm and management of Galerie Genesis, Acacio, unburdened by financial constraints, flourished and prospered in his art and life.

“Luntiang Buhay”

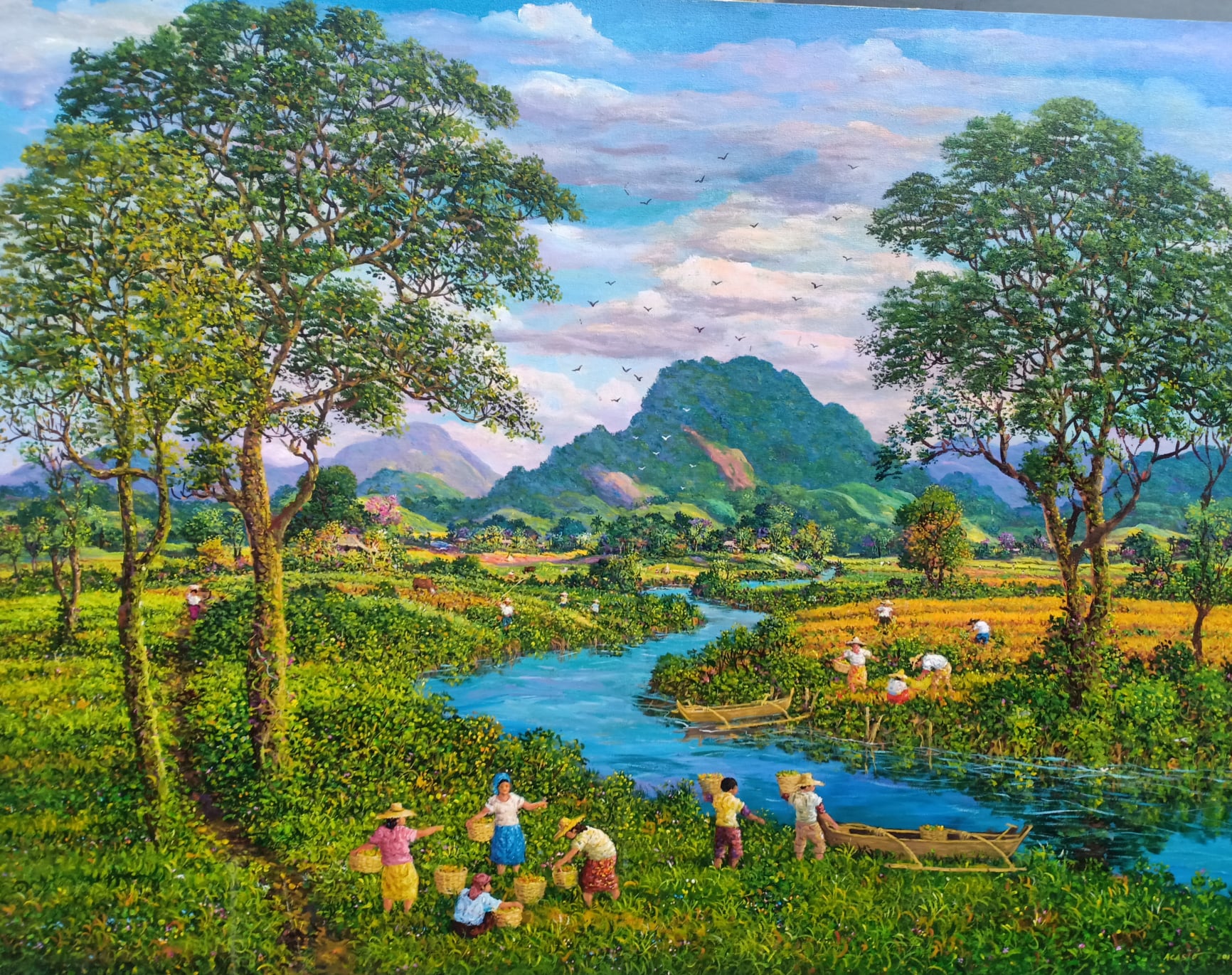

Acacio’s current exhibition at the SM Art Center, organized by Passio Arts Gallery, is only his 6th – his first “Doon Po Sa Amin” was held way back in 1989. This may not give an accurate depiction of this artist’s production of works. It is titled “Luntiang Buhay” – contrasting with the “Luntiang Kapaligiran” series. As evinced by the title, the focus shifts attention to the ongoing life of people living in this idyllic Eden. This may come as a pleasant surprise to those who have been accustomed to the now-classic Acacio landscapes of pure, unadulterated Arcadia, bereft of human presence. These new works are brimming with activities of life, and no better way there is than to merge nature with the innocence of children. Their figures are rendered in miniatures, contrasting with the vastness of the surroundings. One work titled “Saya ng Kabataan” may as well be the show’s titular painting. Their presence transforms the work into something more realistic, distancing itself from previous works that are more suffused with romanticism and idealism.

Another Dimension

To be sure, in an Acacio landscape, one will never catch the sight of a commercial billboard or distant signage of a Jollibee or McDonald’s. Or, for that matter, a Meralco electric post. All such violative visuals – offensive and offending – have in reality become ubiquitous, part and parcel of the Philippine landscape. Still, for Acacio, the intrusion of anything commercial or industrial is anathema, an outright shock to the aesthetic nervous system. While this may lead the viewer to conclude than an Acacio landscape is essentially “escapist” – “fantasist” – a vision from another dimension – well, be that as it may. It may yet be the tragedy of a generation of millennials never to have seen the purity and majesty of nature.

In terms of composition design, Acacio now bisects the pictorial space with an intersecting river or stream, or a winding trail or pathway. One surmises that the device is a way of relieving the thick density of masses of trees and voluminous mountains: a cleft in the constriction of multitudinous brushstrokes, a welcome clearing in the woods. But otherwise, everything else is accounted for: the verdant vegetation, the thicket of trees, the endless vistas, the wide-open skies, the masses of clouds clustering to glorious cumulus, the flooding of sunlight, and certainly, befitting the show, the incandescence of the color green.

All through the life of Lino Acacio, soon turning 63, Nature has always been obliging. In turn, the artist has served her well.

************

Cid Reyes is the author-of-choice of National Artists Arturo Luz, BenCab, J. Elizalde Navarro, and Napoleon Abueva. He has written over forty art books and numerous reviews and exhibition essays. Reyes received a “Best in Art Criticism” Award from the Art Association of the Philippines. (AAP).