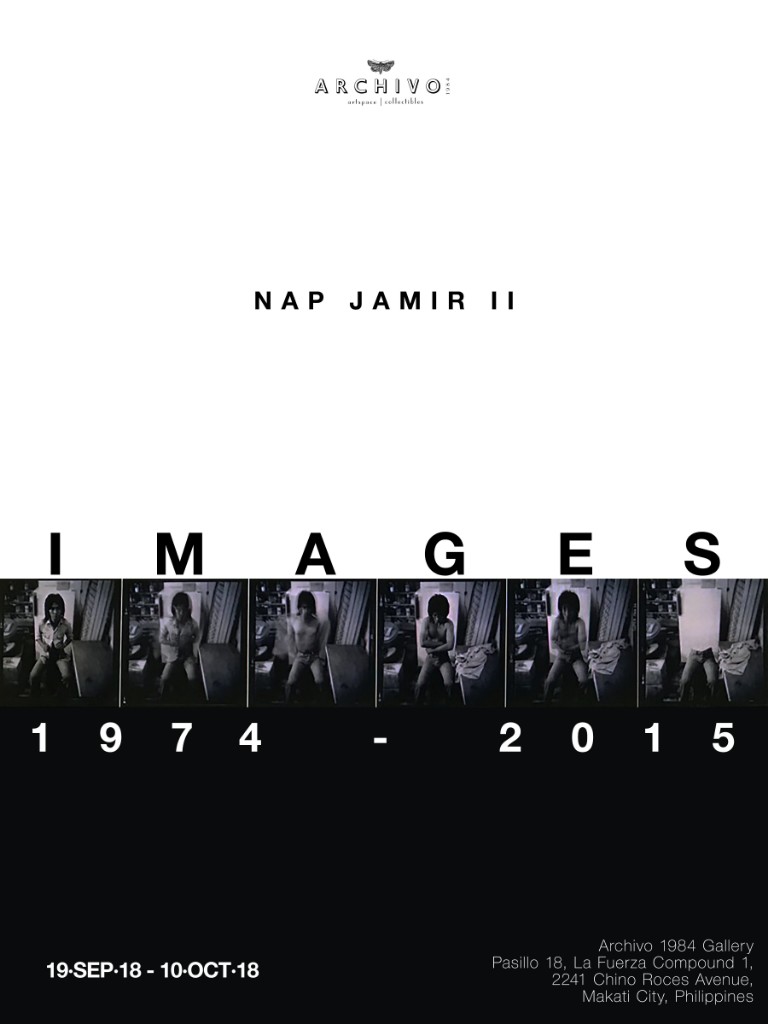

Nap Jamir Images 1974 – 2015

Opening reception on Wednesday, September 19, 2018, 6PM

Archivo 1984 Gallery

Pasillo 18, La Fuerza Compound 1, 2241 Chino Roces Avenue, Makati City, Philippines.

Exhibit runs until, October 10, 2018.

The long view to the work of Nap Jamir II, rara avis

Nap Jamir II is the rare photographer with a Conceptual Art bent. He is indeed (unless I am smacked with evidence otherwise) the only one such artist in the last forty-some years in the Philippines. This seems an outsized claim, sure, but one I am happy to make.

During the advent in 1970’s Manila of contemporary art, I had a perhaps ingénue hope that a few other photographers might have relished exposing the structure of the medium. More, I thought it might be—to use the period word—cool, if photographers did not so much make images, but contrived deliberate marks disclosing the riggings of the photographic imagination under construction. As things transpired since, it was wishful thinking. Filipino photographers to the last man and woman have been visual story-tellers of a humanistic disposition—including those who affect painterly manipulation. And those whose stunning images propose the genius of photography and photographer, are of course masters of narrative. In this field, Jamir is the odd man out. He does not do stunning; never has. He will not narrate.

Except for the still photographs of 1970’s Baguio by the erudite filmmaker Jose Antonio “Butch” Perez—whose iconoclastic attitude towards photography’s trends demands more than a nod here—Jamir has been singular in his attentiveness to photography itself. The medium’s limitations, idiosyncrasies, predispositions, and normativities are his object, which he probes with a curiosity that also seems detached, impersonal. Even when his person enters the frame—often to be made to disappear—he is not self-referential. The body is not “captured” after the fashion of photographic predation that a young Susan Sontag already critiqued during that period.[1] T/his and other bodies are, rather, conjured or materialized, as in fact the emulsion on photographic paper and light sensitive silver halide on 120 mm or 35 mm film strips brush against light molecules that bounced from off here and there. Jamir’s photographs are conceptualized as traces of light grazing surfaces.

Yet to assert so seems heavy-handed. Jamir works with a consistent lightness of touch. He is subtle about how he leaves evidence of his reconnoiterings into photography, on the physical object that photographs are; and hopefully on the spectral presences that photographs become in the minds of viewers. It is clear as I write about this absence of bravura gestures, that his perhaps inadvertent challenge to a writer is also singular: to try to convey Conceptualism sans grand statement-making. His nimbleness around the character of photography demands muted articulation. Since his attentiveness to the medium is by no means that of a scholar probing data, nor of a connoisseur’s scrutiny of technique, it does not seem appropriate for any written response to his photographs to be sophistic or intellectually hard.

Jamir’s Conceptual Art work is best described through the unusual register of sincerity: as the craft of thinking via making, and, vice-versa, photographic making as thinking about photographic making. If the description sounds vaguely dated, it is because the earnest predilection for anatomizing institutions and artistic, political, and scientific work took a strong aesthetic turn during the same 1970’s when Jamir and peers developed a youthful taste for the techniques of interrogation. They happened by Conceptual Art when a mutinous spirit was normal, but philosophical grounding was exotic.

His body of work remains aligned with the Conceptual Art trajectory of institutional criticism. This constancy is useful to acknowledge vis à vis the meta-tenacity of auto-criticism in contemporary art, which has been in place from the moment, half a century ago, when American and European artists mounted strikes against the sterility and deterritorializing modernity inhabiting the white cube (albeit, how long ago this sounds!); the ways of seeing and thinking following undetected infrastructure (albeit, how undetected these constructions remain); and technologies of representation that operate as these technologies were wired to be (albeit, how easily capital keeps re-appropriating these technologies). Jamir—creature of the margins of mid-20th century global contestation when he commenced photographing photography with the mindset of a skeptic—arrives at the 21st century possessed of the DNA, as it were, of postmodernity.

Filipinos observing artmaking in the 1970’s will recall Raymundo R. Albano, Acting Director of the Cultural Center of the Philippines Art Museum during this period, staging mock-heroic interruptions into the space of the grand and gorgeous CCP building; and performing alpha dog to a small menagerie that called itself the avante garde, which notably included Jamir. In hindsight, it was Jamir’s interruptions into the CCP space that ought capture the strange combination of gentleness and spunk of that time. Jamir took photographs of small rectangles of CCP space—a 1:1 35mm analog photograph of, among others, the agglomerated concrete of the building walls, or a part of the paneling, and so forth—printed these with neither enlargement (called “blow up” then!) nor cropping, and pasted these on the same parts whose photographs were taken. The works were all over the CCP. But the photographs were inconspicuous; the work, about as evanescent as art can be. Only a handful noticed. Zero recall, I daresay.

Hauling its recollection into the present exhibition of Jamir, circa 2018, serves only one purpose. I take Jamir’s present exhibition as opportunity to sound a plea for space in art and society for criticality that is not vociferous; that is deeply intelligent and absent of arrogance; that is Conceptual Art more in the spirit of Joseph Kosuth instead of, say, Judy Chicago. Space enough of course for that range. But not, I offer, for the vivid and stagey to overdetermine all art space.

While I describe Jamir’s Conceptualism as vintage 1970s, vintage is not a downside. When he made a horizontal, rectangular, pastel-colorized nude photograph of obese actor a few years ago, he composed by disassembly—by an almost tender tearing of the photographic paper; and framed the two-part assemblage as a neat and nearly seamless-looking whole. The early Jamir is the recent Jamir then, although the skills are profoundly developed now. His restraint in image-making is a sharper critique of image than he managed as a young photographer. Nevertheless the explorations facilitated today by a dexterity enhanced by decades in advertising and filmmaking, preserve an apparently stubborn proclivity towards, well, the gentle tearing at—and of—things. There haven’t been enough gentle anarchists yet. In the arts, especially in photography, I am truly elated that Jamir stayed the course.

Marian Pastor Roces

12 September 2018

Metropolitan Manila

Marian Pastor Roces, independent curator and critic, writes on cities, clothing, museums, international art exhibitions, and politics. She is published internationally. She heads TAO INC, a corporation that has specialized in curatorial work to establish museums, make exhibitions, support urban planners, since 1998.

[1] When Susan Sontag’s series of essays in The New York Times was published as “On Photography” (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), it compelled the more contrary of aspiring writers, photographers, and culture specialists, even in peripheral zones like Manila, to venture to find positions outside mainstream taste and thought. Sontag is mentioned in relation to Jamir specifically because of his work that cannot be appropriated into the predatory language that has been persistently part of photographic practices since the invention of photography.