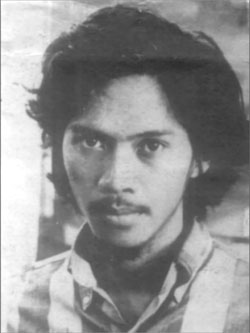

The “Brown Rimbaud”

by Alexander Martin Remollino | Bulatlat • Vol. 2, Num. 44 | Dec 8 - 14, 2002

The tenth of December is marked as International Human Rights Day. The first International Human Rights Day fell on December 10, 1948, when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which declares all people to be free and to have equal rights and dignity and enumerates all human rights, was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly.

On International Human Rights Day, it is fitting to remember the late Filipino writer and revolutionary Emmanuel Agapito “Eman” Lacaba. He was born on the very day the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the UN General Assembly. He lost his life at the height of martial law–a victim of a human rights violation.

Eman Lacaba was born and raised in Pateros. In an essay he wrote as a high school student, “Personal Statement of Emmanuel Lacaba”, which his brother Jose, more popularly known as Pete, believes was written in connection with his application for an American Field Service (AFS) scholarship, he described his family thus: “Our family is neither rich nor very poor. At least we have enough to live on.”

Enfant Terrible

Eman Lacaba has often been compared to the French poet Arthur Rimbaud, a fact he himself alluded to in one of his poems, “Open Letters to Filipino Artists”, where he told of his being called “the brown Rimbaud.” The comparison stems from the fact that he was, like Rimbaud, an enfant terrible, a literary virtuoso at a very young age–he started writing poetry at 14—and did so like a master even then. The similarity between them became all the more striking when he lost his life without reaching his fortieth year–just like Rimbaud.

He began to display vast and varied talents at a very young age. He learned to read early and was a very voracious reader before he was in high school—reading everything, as he said, “from the Bible to Mad, from newspapers to encyclopedias, from physics to law and business books, from mathematics to poetry.” From first grade to his last year in high school, he was at the top of his class. A brilliant and prolific writer at a young age, he became editor-in-chief of the high school paper. He was also a versatile athlete; he

played basketball, soccer, and was into track and field. He was an excellent actor on the stage. In recognition of his leadership skills, his schoolmates gave him many of the top positions in school organizations–he was class president from fifth grade to his last year in high school, he became president of the High School Drama Club and the High School Student Council.

He received almost all of his pre-university education from the Pasig Catholic College. While still a student of this school, he applied for and received an AFS scholarship, through which he got to spend an entire school year in the United States.

After high school, he had the chance to choose among no less than three scholarships from the University of the Philippines (UP), the Ateneo de Manila University, and De la Salle University. He chose the Manuel de Leon scholarship at the Ateneo de Manila University, where he took a Bachelor of Arts in Humanities, and maintained it until he completed his course. This, despite the fact that he spent much of his time away from the classroom, writing or doing research.

Writer-Activist

If there is something Eman Lacaba is most noted for, it is for having been a writer-activist. He was a poet, essayist, playwright, fictionist, and scriptwriter who joined the protest movement in his student days and later lost his life as an armed revolutionary.

It was at the Ateneo that he began to be involved in social and political causes. He was part of a group which fought for the Filipinization of the university administration, which was then largely American-led, and the use of Filipino as medium of instruction. His group also called on their schoolmates to immerse themselves in the issues which had begun to galvanize their fellow students at UP.

In his early days as an activist, his poetry began to show signs of the road he was to take for the rest of his life, with his increasingly frequent use of the image of Icarus, a Greek mythological character who burned his wings, fell to the sea, and died because he flew too close to the sun–an often-used symbol for those who perish in the pursuit of lofty causes.

He also joined Panday Sining, the cultural arm of the militant Kabataang Makabayan, and is believed to have participated in the First Quarter Storm.

In his college days he frequently commuted between the Bohemian life and activism. It was only after college that he would turn his back on the former.

Before he graduated from college, he won a major literary award for Punch and Judas, a short novel depicting the transformation of an intellectual, Felipe “Philip” Angeles, from Bohemian to activist.

After college, he taught Rizal’s Life and Works at UP and got involved in the labor movement. He also became a member of the militant writers’ group Panulat para sa Kaunlaran ng Sambayanan. Just two months before the declaration of martial law, he was among a number of picketers at a small factory in Pasig who faced threats and truncheons from the police while the strike was being dispersed. He was arrested and briefly incarcerated.

After that, he became active on the stage, writing and acting in plays. He also assisted in film productions, and among his compiled writings are a number of unfinished film storylines. He wrote the lyrics for the theme song of the Lino Brocka-directed movie Tinimbang Ka Ngunit Kulang, which takes potshots at the hypocrisy of society.

In 1975 he set out for Mindanao to cast his lot with the armed revolutionary movement, to become a “people’s warrior”, as he later called himself in a poem.

Such was his passion for writing that he wrote even while leading the life of a revolutionary guerilla. It was in the hills, in fact, that he wrote one of the poems he is best remembered for, “Open Letters to Filipino Artists”, where he wrote of the armed revolutionary movement thus: “We are tribeless and all tribes are ours./We are homeless and all homes are ours./We are nameless and all names are ours./To the fascists we are the faceless enemy/Who come like thieves in the night, angels of death:/The ever moving, shining, secret eye of the storm.”

Death of a People’s Warrior

At dawn sometime in March 1976, death came for Eman Lacaba. At this time he was set to go back shortly to the city for a new assignment that would have used his writing skills, and had even agreed to write a script for Lino Brocka once he got back there.

It was not yet six in the morning. Eman and three other companions were having breakfast in a peasant’s hut. Outside the house were their wet clothes and shoes, left there to dry.

Elements of an armed team made up of Philippine Constabulary (PC) men and members of the Civilian Home Defense Front (CHDF) were with a certain Martin, a member of Eman’s unit who had earlier been captured by the military. They happened to pass by the house where Eman and his companions were having breakfast. Martin recognized the clothes and shoes and pointed out the house to the PC-CHDF team, who immediately opened fire without calling on the occupants to surrender. After a brief gunfight, two of the hut’s occupants were killed including the leader of Eman’s group, while Eman and Estrieta, a pregnant teenager, were wounded.

The PC-CHDF team headed for Tagum with Eman and Estrieta, with villagers carrying the corpses. However, a few kilometers from the village, the sergeant of the PC-CHDF team decided not to bring back anyone alive. Estrieta was the first to go. The sergeant then handed a .45 to Martin and ordered him to shoot Eman. He did not want to, but in the end Eman himself said to him, “Go ahead, finish me off.” A bullet was fired through his mouth, crashing through the back of his skull. As he fell, another bullet was fired at his chest. He was 27.

Source: Bulatlat.com