An attempt to understand the Visual Poetry of Dr. Epitacio Ramos Tongohan, MD aka Doc Penpen Bugtong Takipsilim

By: Noel Sales Barcelona

Visual poetry, in the past 2,000 years, is one of the most amazing inventions of poets and writers in ancient times. The manipulation of words or characters to create images has given poetry and prose new power, not only in terms of aesthetics but also in semiotics. From the technopaegnia of Ausonius to the present e-poetry, this type of poetry empowered both the writers and readers as they give new flavor, understanding, and appreciation to the art and science of writing poems.

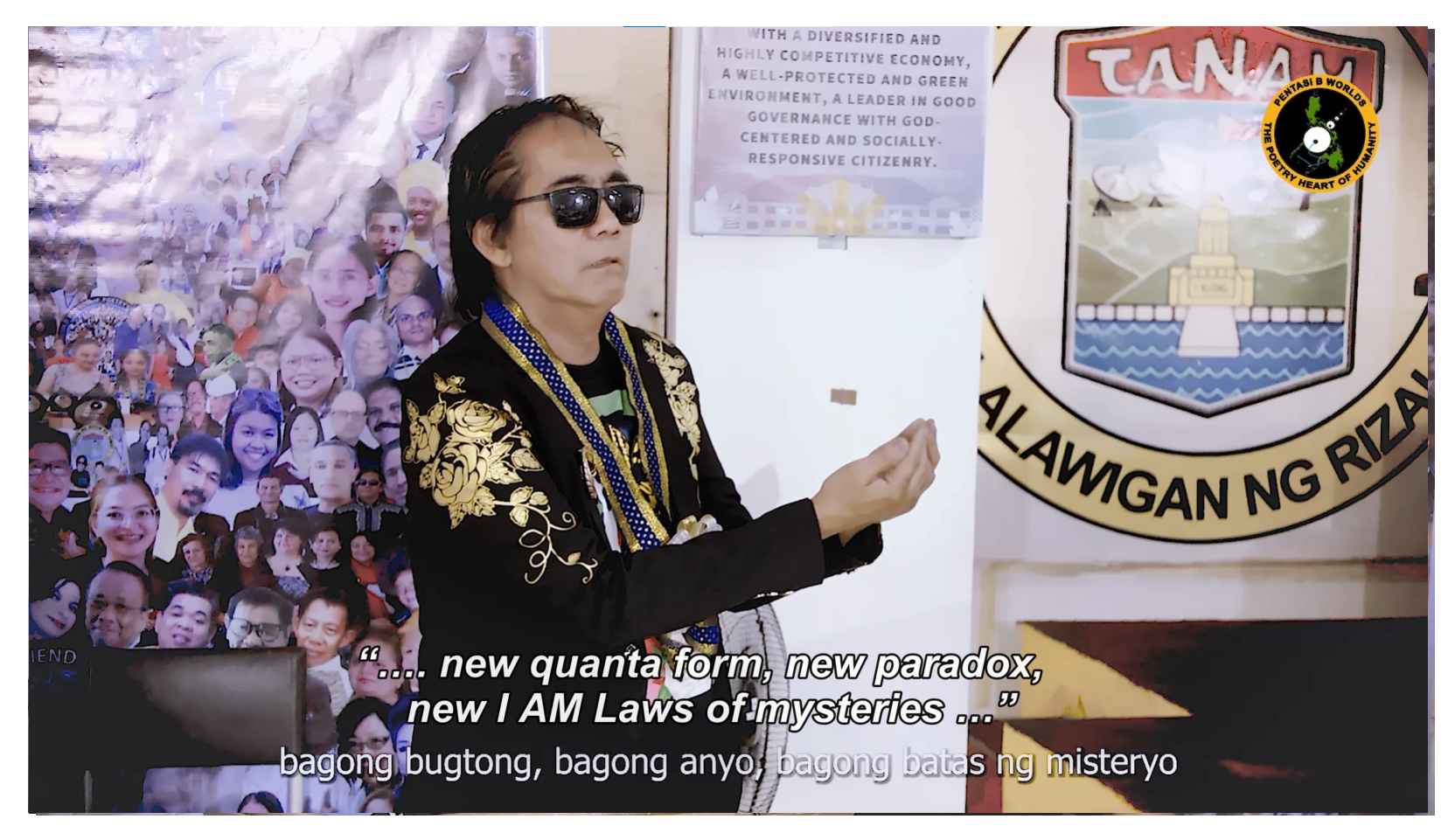

Interestingly, there is one person who is said to have mastered the art and science of visual poetry that poets all over the world gave him the prestigious title “Father and King of Visual Poetry.” He is Dr. Epitacio Ramos Tongohan, a medical doctor and a pathologist born and raised in the humble town of Tanay, in the Province of Rizal, in the Philippines. Known by his pseudonym, Doc PenPen Bugtong Takipsilim, or simply Doc Penpen, Tongohan has introduced to the world a new type of visual poetry which, according to his readers, has a life and soul of its own as it moves, allegedly, form the pages where they were written. Furthermore, the impact of his visual poetry is also enormous as it affects the mind, body, and spirit of those who read them.

This short essay will attempt to dive into some of the verses written by Tongohan that I found on the internet and analyze them semiotically based on the supposed innate and “hidden” meanings found “inside” and “outside” the examined verses. If there are some shortcomings, my sincerest apologies.

***

Text and soul freedom

There is one poem by Tongohan that we have encountered published by the Fund for Cultural Education and Heritage in 2016. The verse goes like this:

yes !am

yes i am free

yes free for all

i am beyond the walls

beyond the pages

beyond the bitterness of man

i am the best of all

the best of all dreams of all hopes of all wishes

i am the greatest revelation of all-unending-self-discoveries

i am the core of every infinite evolution of existence for perfection

i simply live

f r e e l y

in every birth in every death

in every breath of the universe

i am LOVE

without a temple

without a name

However, based on the timeline, this poem was produced by Tongohan or Doc Penpen in 2013.

The simplicity of the presentation cannot hide the depth and breadth of the verses, with all lines written in small letters.

In ancient times, philosophers, magical priests, and sages see human beings as the mirror of higher reality. Inside of Man resides the bigger universe, hence, he was considered as the microcosm—the exact but scaled representation of the Cosmos itself. As the Cosmos signifies the very “mind” and “reality” of God—the Alpha and the Omega—or the very reason that everything exists and ceases to exist, it means that Man, as the microcosm, is also considered as the powerful co-creators and manifesters of both internal and external realities. However, one must realize this potential. And to realize this is to take a deep dive into the realm of the Consciousness or the existing and manifested Spirit, which resides within us.

In Tongohan’s poem, the poet proclaims not only the freedom to create verses but also expresses the discovery of the unbounded and full-of-potential energy that resides within the very core of a human being. This, in religious and mystical terms, is called the Spirit-Soul, the Higher Self, or the Superconscious, which shares the same characteristics with the substance that constitutes the Supreme Being, the Unmanifested Creator. Reading closely, one will realize that it is no longer the poet who writes the poem but the Soul. The prompting is no longer about the physical body and the “material” mind (which is represented by the brain and all its functionalities, including the processes of the nervous system) but the Spirit. On the other hand, the poem can also be considered an expression of self-realization (knowing one’s true nature and life’s purpose) and self-actualization (realizing one’s full potential as a human being).

Interestingly, Tongohan has to end the poem with these lines:

i am LOVE

without a temple

without a name

The lines mentioned above describe what we call the Agape, or the divine love, which is all-encompassing and eternal. The poet now penultimately describes the Self (this time, we mean the Superconscious, the Higher Self, or the Spirit Soul) as the nameless, boundless, and endless representation of that kind of Love, which is the very nature of the Creator itself.

The Poet Amid a Catastrophe

There is another interesting verse that this poet crowned as the Father and King of Visual Poetry by different poet groups in various parts of the globe that he titled “But Up)”. This poem, according to the information available at PoemHunter.com, was penned during the aftermath of Ondoy (international name: Ketsana), which devasted major parts of the Philippines in 2009.

The poem goes like this:

GO where i fall in midst of mist

of why TO be or not to be so many why why me

im in the PLACE of hundreds thousands lists twist to exist

in drowning mud of floating coffins im mad NO light i see

loved ones all gone im down so down and all i HAVE my fists

kissing my knees flaming-in-midst-of-i of fallen-i-in-mist dried-i go where: (I

At first glance, you may see the poem as a verse describing loneliness and despair as it was penned after the super-typhoon Ondoy left millions of Filipinos homeless and claimed the lives of more than 300 people. But examining the verse closely, this poem is a poem of hope and strength.

But the Filipino as a race is known for their resiliency and buoyant spirit. In his poem, the poet embedded the words “I have no place to go” in the lines of his poem. But as I have mentioned before, while the poet aired his feelings of despair, and perhaps, hopelessness as signified by the “invisible” phrase “I have no place go,” written from bottom to up, it is the necessity for resiliency, pliancy, and courage that has forced him to transcend from these negative thoughts and feelings brought by the catastrophe. There is no other way but to go up; and if you have fallen, you need to stand up and move on. This is the only way to go.

One must note that this is not all about toxic positivity. But for me, this is an encouragement to face the bitter truth that you need to face the issue, conflict, or problem (this time, the negative experience brought by a natural catastrophe), and process it so that you can have them resolved. To wallow in despair is not a good thing to do. While recognizing that there is pain and suffering due to an unfortunate event or circumstance, there is a need for you to gather yourself together, hope for the best, and slowly work yourself up so that you can transform this tragic event into a catalyst of self-growth.

I cannot help but quote Jewish psychoanalyst and Holocaust survivor Dr. Viktor Frankl:

“The pessimist resembles a man who observes with fear and sadness that his wall calendar, from which he daily tears a sheet, grows thinner with each passing day. On the other hand, the person who attacks the problems of life actively is like a man who removes each successive leaf from his calendar and files it neatly and carefully away with its predecessors, after first having jotted down a few diary notes on the back. He can reflect with pride and joy on all the richness set down in these notes, on all the life he has already lived to the fullest. What will it matter to him if he notices that he is growing old? Has he any reason to envy the young people whom he sees, or wax nostalgic over his own lost youth? What reasons has he to envy a young person? For the possibilities that a young person has, the future which is in store for him?

No, thank you,’ he will think. ‘Instead of possibilities, I have realities in my past, not only the reality of work done and of love loved, but of sufferings bravely suffered. These sufferings are even the things of which I am most proud, although these are things which cannot inspire envy.”

At least for me, the above quotes from Frankl can best describe the lines of Tongohan’s poem.

Attaining Oneness with everything

The last poem that caught my eye is also from PoemHunter.com. The poem goes:

uh nothing when nothing

came into an end

recycled-its all-transformed-its

all-laws-reborn: : its-death-rebirth

to new-old-new-old-thoughts when every little thing

fell into a vacuum of unwritten memories

for no time to spare

in that timeless cage

of emptiness of boredomness

of nothingness

i stopped to write

)

but when yes when but how right here right now

yes i yes when i look again at this empty space

across this page of total blankness

i see a dot

i see a new page

(

uh i start to write

for now i see

myself

again

In Buddhism, total emptiness or Nibbana is the ultimate goal. To achieve Nibbana, one must detach oneself from things that are considered temporary. Through detachment or not clinging to temporary things—from material things to thoughts and companionships—one can liberate the self from being caught in the web of birth, rebirth, and death.

“In the language of the Buddha, the word for fuel and for clinging is the same: upadana. The Buddha understood that suffering arises from and is fueled by clinging. When the fuel is removed, suffering is extinguished. By understanding how deep-rooted and subtle clinging is in our own unliberated minds, we come to appreciate the mind of Nibbana as refreshingly cool and peaceful,” says an article published by the Insight Meditation Center website.

It seems that Tongohan’s poem quoted above represents the attainment of the goal of being in complete stillness and emptiness, wherein the ebb and flow of thoughts, emotions, and actions eventually ceases. The poet, therefore, has been able to remove himself from the casing of temporariness and in the constant chasing of something that is temporary and fleeting, and eventually achieved total tranquility.

Meanwhile, in Vedic philosophy, the verse can also mean the attainment of perfect union with God or the Divine. This union, however, can only be attained by the complete knowing of God and our relationship with God. In Bhagavad Gita, for example, it says:

One who knows the transcendental nature of My appearance and activities does not, upon leaving the body, take his birth again in this material world, but attains My eternal abode, O Arjuna.

The eternal abode of God, or in Christianity, God’s kingdom is the ultimate place of eternal happiness. The coming and going of negative emotions will stop, the curse of birth, death, and reincarnation will cease, and the oneness with God will eventually be realized. This oneness is complete; therefore, the materiality of our nature will also cease as the temporal casing that holds the soul as a prisoner of material desires, which constantly bring us unhappiness and discontent, will be dissolved. With this dissolution, as the poet suggests, the “writing of poems” will stop.

On the other hand, the rediscovery of oneself, in its truest form—the Pure Consciousness for the Buddhist and neo-spiritual beliefs or the Spirit Soul for the Hindus, Christians, Jews, and Moslems, will give way to the continuity of the most beautiful poem that one can ever write: And that is being one with the Greatest Poet, which is the Divine Providence.

By means of a conclusion

While I have been able to read just three of the available poems that this poet from Tanay, Rizal, available online, we can say that his visual poetry is humanistic transcendentalist poetry.

Humanistic for most of them focuses on the goodness and the capability of humanity to love and care for each other and even for other beings that are part of this physical or material universe. This goodness and compassion are considered innate or natural to all of us, as we have hearts that are beating and feeling.

Meanwhile, his poesis can be considered transcendental, for they also focus on the divinity of the human person and even of other beings that surround him. Because the spirit of God dwells in every living being, there is a strong connection that happens between them. This connection is made possible by Agape, that kind of transcendental love that knows no boundaries and no end.

However, I admit that this essay only scratches the surface of Tongohan’s “brand” of visual poetry, which earned him the prestigious title of the Father and King of Visual Poetry by poets worldwide. Hopefully, we can get our hands on the three-volume anthology that Tongohan published several years ago so that we can have a better grip and understanding of his visual poetry.